Philippines Report

What did we find out ?

A. Health literacy materials available in the community on COVID-19 prevention and cure

Most health literacy materials consist of communicating the protocols from the local government units (LGUs), also referred to as official public signs. Other health literacy materials include visual posters produced by private establishments such as service shops and businesses, social media posts, social media messaging, and videos on online platforms. These health materials are mainly produced in the form of tarpaulin banners, physical or digital posters and video clips.

1. Health literacy materials from the local government units (LGUs) and business establishments

Most of the participants stated that they used the health literacy materials from their local government unit, particularly the city offices and the barangay of their own respective communities, as COVID-19 safety warning signs. These health literacy materials contain the quarantine protocols and other health reminders necessary for the prevention and cure of the coronavirus. These materials are being reproduced in the form of tarpaulins, stands and posters that are placed along the streets, in business establishments and government offices.

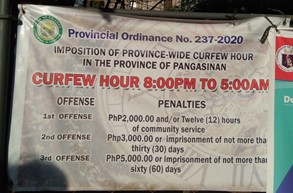

Figure 1. A tarpaulin poster showing the provincial ordinance in Pangasinan stating the curfew hours

Figure 2. A health stand placed inside a mall in Pasay City

In the rural area of Calasiao, Pangasinan, most families rely on the health literacy materials placed within their neighbourhood. Figure 1 is an example of how city mandates and other pandemic related announcements are being turned into visual materials by the government to make them easily accessible to people across all sectors. Similarly, in Maricaban, Pasay City, most participants stated that they relied on health announcements converted into visual material, as shown in Figure 2. The health literacy materials collected for the purposes of this research were mostly in English, one of the official languages of the country, alongside Filipino. This finding illustrates that English institutionalized as the main language of communication used across all sectors.

Both communities rely heavily on the health literacy materials produced by the government. The COVID-19 safety warning signs produced by LGUs were more accessible to the participants than other sources of information, as they were disseminated in both public and private establishments. Accessibility to reliable information is a crucial factor in limiting the spread of the coronavirus. Therefore, the two communities only retrieved information coming from the LGUs since mandates and health statistics were directly retrieved from the national government data report.

2. Social media posts, social media messaging, online videos

Significantly, members of both communities utilised technology-related tools in accessing and sharing health literacy information. Most popular have been social media posts on the Facebook platform, due to being very accessible to both communities. According to the families, trending posts will usually catch their attention. These social media posts include a variety of photos, content posters and short video clips or vlogs which contain protocol-related reminders, pandemic-related news and prevention and cure against the coronavirus.

Although most of the health literacy materials retrieved from the participants came from Facebook, Facebook Messenger, via group chats, was also widely used. Participants also mentioned YouTube as a source of content related to the pandemic and some use Viber as an alternative social messaging platform.

Figure 3. A digital poster which shows a pandemic-related protocol from Pasay City’s LGU Facebook page

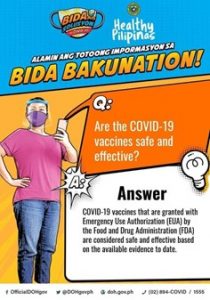

Figure 4. An infographic poster from the Department of Health (DOH) Facebook page

Figure 5. A screenshot of a vlog about community pantry in Pasay City posted via YouTube

With the emergence of digital technology, access to fake news is rampant in the social media realm. However, both participant groups stated that they rely heavily on the visual materials produced by the government. These health materials or official public signs adopted the official mandates and drew on the official statistics produced by the Department of Health (DOH). To be specific, they tended to rely on credible sources such as those from the Department of Health (DOH) or their local city’s official Facebook page. Figures 3, 4, and 5 are examples sent by the participants.

Again, there were a handful of signs in Filipino but English was the dominant language used. Although English is one of the official languages of the country, Philippines is known to be a multilingual country; hence, it should cater equally to diverse speech communities. However, findings from this report revealed that communicating health-related information in the Philippines relies heavily on the English language which cuts across institutions, industries, and other societal sectors.

B. Local and indigenous practices related to COVID-19 pandemic and other healthcare systems

This section covers the local and indigenous practices related to the COVID-19 pandemic and other healthcare systems in the two participant groups. These practices and community pandemic strategies include the use of alternative medicines and reliance on faith practices. National and local government responses were also retrieved, alongside the pandemic aid from NGOs and other forms of community support as multi-sectoral responses

1. Reliance on faith

The Philippines is strongly influenced by religion, particularly Christianity and Roman Catholicism. During the COVID-19 pandemic, most families relied heavily on their faith as the backbone of their hope and as prevention against and cure for the coronavirus.

Based on the health literacy materials received from both participant groups, prayers are posted via the social media platform, with Facebook being the main source. Others visit Churches on-site to get near the relics of the Lord and/or images of the Saints. According to them, their faith has been their main source of strength in times of hopelessness as they have battled against an invisible virus.

Figure 6 shows examples of prayers posted online. According to one of the participants, their family tends to rely on prayers, asking for divine intervention to protect their families against COVID-19 and for healing.

Figure 6. Screenshots of prayers from the Twitter platform

Figure 7. Images of Jesus from a Catholic Church in one of the research sites

In one the research sites Maricaban, Pasay City, most households, specifically the mothers, will visit their Parish or nearby church in conjunction with the protocols strictly implemented in the community, such as social distancing and the wearing of face shields or masks, COVID-19 contact tracing and thermal scanners. As lockdown restrictions eased, they would get as close as possible to Church, sometimes involving driving to the outside parameters of the Church – simply to make prayers of supplication and healing. Figure 7, retrieved from one of the participants, are images of Jesus. The left photo is an image of the baby Jesus or Sto. Niño. The right photo, on the other hand, is an image of Jesus of Nazarene or Nazareno Jesus (in the local language).

Figure 8. Parishioners in Calasiao during a procession of the monstrance, the vessel used by the Catholic Church to display the consecrated Eucharistic host.

Figure 9. Eucharistic adoration in Calasiao, Pangasinan

The rural community in Calasiao, Pangasinan is heavily dominated by Catholic. Figure 8 shows one of the practices as an alternative of the Parishioners during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, parishioners would visit the Church on-site to receive Divine Grace. However, when movements were limited during the pandemic, all on-site activities were suspended. Instead, priests travelled in caravans or motorcades to visit the believers outside their homes. Figure 9 is a photo retrieved from a participant in Calasiao, Pangasinan. It is the Eucharistic adoration practice where the Parish priest lifts the Body of Christ, under the appearance of bread placed in a sacred vessel, called the

2. Alternative medicine and traditional practices

Key findings in this study pertain to the use of herbal products and alternative medicinal practices to prevent and cure the coronavirus. The Philippines is known to be rooted in traditional practices, especially when it comes to health care related systems. Most Filipino families have used these practices during the pandemic.

Some participants tried using Lianhua Qingwen to cure their COVID-19 symptoms. Lianhua Qingwen is a traditional Chinese medicine used originally for the treatment of influenza. Ivermectin, an antiparasitic medication used to treat scabies, river blindness and ascariasis among others, i.e. human parasitic infestations, was also used by a handful of participants as a cure. Other participants were against the use of Lianhua and Ivermectin, due to the lack of evidence that it can cure COVID patients, while others remained to their belief that these alternative medicines can cure symptoms against the coronavirus.

Both participant groups stated that they relied heavily on the use of steam intake ( suob/tuob in the local language) as they believe that this practice helps with the respiratory breathing problems that are a symptom of COVID-19. Steam inhalation is generally used to clear nasal congestion. The participants described the practice of holding their heads over a bowl of steaming hot water with salt.

Lagundi, also called Chinese chaste-tree, is a herbal medicine used to treat coughs and fevers; participants took it in capsule form, as tea infusion or as a powdered solution. Menthol has been used to ease headaches or dizziness and for muscle pains. Additionally, some have used honey to ease a sore throat or cough. This is often mixed with citrus fruits such as lemon, orange and calamansi in a cup of warm mater.

C. Response to national and local government mandates

Most participants expressed concerns about the national and LGU COVID-19 mandates and protocols. According to them, most LGUs directly adopted the national protocols and statistical data. However, there were sometimes problematic gaps in the implementation of the legislative framework, with some LGUs being stricter than others. Participants also expressed concern in relation to brands of alternative cures such as Vitamin C.

According to a health worker from Maricaban, Pasay City:

“Branded or not, it’s the same. It depends on the person who is receiving the treatment. If it’s totally worse, maybe there’s no need to use a generic brand. All of you are comfortable with using branded medicines; however, in our community, although others still have this mentality that generic medicines are not effective, since branded medicines are considered to be more strong. But what Dr. Ben will always remind us, it’s just a matter of mentality. Since a lot of people have been comfortable with using branded medicines. But here in our house, I have been applying the same mentality to raising my kids using generic medicines. In God’s mercy, they are all okay. I believe that it’s just a matter of perception. Regarding vitamin C, it depends. What Doc always advises us is to use it to boost the immune system. Others actually have been drinking only half of the prescribed dose of vitamin C so it won’t be dangerous to the kidneys. However, others will be told to take twice the dosage. It depends on the patient, on a case to case basis.”

A pharmacy graduate in Calasiao, Pangasinan, agreed that a generic vitamin supplement was no less effective than a brand:

“On the branded versus generic medicine, Ate is right. In terms of the medicine formulation, pharmaceutical companies have been using a master book that serves as their basis. That’s why there is no problem between choosing a branded or a generic vitamin. With regard to vitamins used, there was a time here in Calasiao when vitamin C went out of stock due to panic buying in the middle of the pandemic. Usually, 500mg is the right dosage per day. However, people went on a ruckus and have been taking 1500mg per day. With regard to alternative medicine, it’s good to know about the use of lagundi, sambong. These are really helpful for other illnesses. However, there are medicines that cannot totally heal ailments. Also, as Doc said earlier, there are medicines which do not have therapeutic claims to individuals. That’s why it is still better to have a formal consultation with a doctor, since there may be ailments that a certain alternative medicine is really not compatible with, especially when you just heard of it.”

Aside from taking vitamin C, prevention practices included putting in place similar protocols within their homes, “family rules” before entering their homes. For example, a health worker from Maricaban, Pasay City stated that:

“Before going inside or into the sala, my husband changes his clothes just once a day. It’s a given that men are not so meticulous when it comes to their bodies. However, my youngest son always uses alcohol, spraying it all over his body when entering the house after spending some time outside. The only difference is that my husband is not a fan of using alcohol spray. You still need to remind him before entering the house that you should wash your hands first, and don’t walk inside the house with your shoes on. Even everyday, you still need to remind him not to walk inside the house with his shoes on, because men are not conscious even if the house gets muddy. You just need to wipe it with Zonrox thereafter, since you can’t do anything about it. It’s like you’re always guarded.”

Overall, aside from utilizing health literacy materials and alternative health practices, the families adopt COVID-19 prevention strategies based on their beliefs, experiences and knowledge

D. Programmes and other forms of aid to support communities during the COVID-19 pandemic

The national, local and non-government organizations (NGOs) provided assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although LGUs have provided financial support through ayuda (financial subsidy) and relief goods, the NGOs have been the largest contributors in providing relief. The experience of the Philippines in the pandemic is further evidence that it takes a multi-sectoral response to effectively mitigate the spread of the virus and provide assistance to communities that are struggling economically.

Figure 10. A nun from Maricaban, Pasay City shows how to make a DIY face mask

In Pasay City and Calasiao, a religious congregation run by Dominican nuns taught their partner communities how to make face masks as their contribution to helping those people living within their congregation s vicinity to contain the spread of the virus and to help communities with their livelihood during the pandemic. Below are examples of their DIY face masks:

Figure 11. Face mask samples from the nuns in Maricaban, Pasay City

Parish leaders and youth leaders in Calasiao, Pangasinan have also provided food relief to the communities in the vicinity of the parish to help ease the communities’ economic struggle.

Figure 12. Relief goods distribution with representatives from the local government unit (LGU) in Calasiao, Pangasinan

Financial constraints and lack of resources remain a prevalent challenge and have been exacerbated by the pandemic. According to participants, individuals and organisations have been generous in the provision of aid to communities heavily affected by the pandemic. This suggests that the knowledge and learnings retrieved from healthy literacy materials, e.g statistics of COVID-19, can pave the way to a multi-sectoral response. In other words, knowledge alongside existing sets of beliefs has been translated into meaningful actions to alleviate the challenges brought about by the pandemic.

What are our recommendations for policymakers and practitioners based on these findings?

The Department of Health (DOH), together with national agencies and local government units (LGUs), strengthened their public health education response for the detection and prevention of the coronavirus through the Philippines COVID-19 Emergency Response Project (PCERP). The government institutionalized the “Bayanihan to Heal as One” or “We Recover as One,” developed by the IATF-TWG for AFP, to alleviate the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic. Moreover, in collaboration with the LGUs, the Philippine national government has been using varied types of media, such as social media platforms, to raise awareness amid the strict implementation of quarantines.

Key findings from the study can be categorised into four themes: 1) both communities have used health literacy materials from the LGUs and on social media platforms; 2) local and indigenous faith and health practices, including alternative medicines, have been key to alleviating fear and anxiety about the coronavirus; 3) intergenerational views and practices have helped to mitigate the spread of the virus; and lastly, 4) the multi-sectoral response through financial aid and support has been the backbone of efforts to alleviate the economic challenges.

Successful mitigation of the virus relies heavily on the joined up actions of government and its people. Hence, literacies that focus on health, healthcare and health systems must be prioritized in a pandemic. Apart from the accuracy of health information and the credibility of health-related resources, critical awareness in processing and engaging with health information and health providers is also crucial. The World Health Organization (1985) has long argued for the importance of health promotion, especially during epidemics. Therefore, health education must be critically pursued to provide platforms that provide sustainable access of information to communities.

To alleviate the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic, and to effectively implement the “Bayanihan to Heal as One” or “We Recover as One” act, developed by the IATF-TWG, the following recommendations are made:

- Annual allocation of health funds to ensure that hospitals can serve as main facilities for COVID-19 patients

- Special budget allocation for mass testing and purchase of vaccines

- Support to local government units (LGUs) and non-government organizations (NGOs), such as congregations and parish communities, to aid relief and financial support

- Support to provide credible, effective, and comprehensible health statistics, health protocols and mandates, and other health-related materials published on-site and produced via social media platforms

- Provide knowledge and skills in coping with Covid 19 for the whole family, especially for parents and caregivers, aimed at developing health literacy and family learning through webinars, seminars and content videos which can help to determine best practices against the coronavirus

- Provision of other health-related benefits like healthy and nutritious food for senior citizens and children; physical activities for families to improve their health; or recognition of families who have managed to keep their living areas clean; build upon intergenerational and indigenous learning

Methods

This study adopted a descriptive-exploratory research design to gain an understanding of health literacy and family learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study explored how the policies and programmes in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic could develop creative and critical health messages that build upon intergenerational and local learning. Using qualitative methods, the study analysed participants’ access to and engagement with health literacy materials and providers within families, communities and mainstream and non-mainstream media. It employed combined desk research analysis of health materials, interviews and focus group discussions to generate themes relevant to the study’s aims.

Research participants

Participants were from two communities situated in Calasiao, Pangasinan and Maricaban, Pasay City in the Philippines, both heavily affected by the COVID-19 crisis. Calasiao, Pangasinan is an agricultural area in the northern part of the Philippines. Agricultural crops in the area include rice, corn, mangoes, bananas and vegetables. Other forms of livelihood are hat and mat weaving, native rice making and bocayo production (sticky candied coconut strips). Maricaban, Pasay City, in Metro Manila is a highly urbanized community where most of the families are considered informal settlers. The area is deemed as one of the most depressed areas in Pasay City. Livelihoods include selling cooked meals, driving pedicabs (a pedal-operated tricycle with an attached covered seat for 2-4 people) and ‘house-helping’ as stay-in helpers.

The data for this study were collected through qualitative means such as interviews, focus group discussions, and document analysis (materials shared by participants). Participants were chosen from communities served by a non-governmental organization (NGO) whose priority areas include health care and nutrition. Site selection was purposive as an urban and a rural community were chosen. Interestingly, these are the mission areas of one of the mentees of the 2-month mentorship programme titled, Family Literacy and Intergenerational Learning: A mentorship programme under GCRF 1 project.

Initial and informal online meetings were conducted first with the head of each family and representatives from the two communities. The objective of these preliminary meetings was to build rapport with the participants, and to discuss their expected voluntary participation in the data gathering process. Online focus group discussions (FGDs) were scheduled with the assistance of the field workers of the study: a) A representative in Calasiao who is a parish leader, and b) Two representatives in Maricaban who are health workers. The focus group discussions, named as Kumustahan sessions, were conducted with ten heads of households from Calasiao and Maricaban, including both youth and adults via the Zoom platform. A total of six Kumustahan sessions took place, three in each community. Verbal analysis from the participants was included to determine how they process, evaluate and communicate health information.

Creative and action-oriented workshops were also held, titled “Youth for Health: a month-long learning and exchange of best practices,” which aimed at recognizing the potential of young people as contributors to nation and community building. These took place in five instalments via the Zoom platform. The main goal of this series of workshops was to develop health literacy programmes and advocacy materials produced by youth leaders to take forward health literacy and intergenerational learning within their respective communities. The culmination was an event involving a stakeholders’ forum with the communities — LGUs, DepEd representatives and parish ministries. A webinar was also conducted on mental health and family relationships.

In addition to the interviews, FGDs and workshops, documents and health literacy materials were requested from the participating families and communities, including: executive orders, city and provincial ordinances, barangay mandates; various forms of media such as videos, public messaging through barangay megaphone recording; visual materials such as printed tarpaulins, standees, and posters, and social media posts. An analysis of these health information materials was conducted to further address the aims of the study.